Lani:

After one month of Filipino insanity, I found myself in the Chinatown district of Kuala Lumpur. This was an entirely new city for me, where restaurant workers hollered orders of chicken curry over the muezzin’s call to prayer. The Chinese shop owners sold cheap bottles of whiskey, medicinal herbs, and manga. The Malay ladies, draped in pastel headscarves, shuffled into shopping malls to escape the jungle heat. And I was traveling alone for the first time on our trip.

Yup, I was alone. Jared was still in Manila. This was because, of course, Jared’s passport had been stolen in the Philippines. When you lose your passport abroad, you’re thoroughly screwed because you need to not only replace your passport but also obtain a new tourist visa. And, if you’re in a city like Manila, you need to deal with the bumbling and highly corrupt officials from both the Filipino police force and immigration authority. Not an enviable position. Since at least one million things could go wrong, Jared and I knew that he would potentially miss our flight to Malaysia. If that happened, I would still go to Kuala Lumpur. He would meet up with me later.

Well, needless to say, Jared didn’t make the flight. He wrote a hilarious post about his experience, which I recommend you check out. And, as for me, I felt a mixture of regret and deep relief to leave the Philippines behind.

My hostel in Kuala Lumpur was centrally located — a fifteen minute walk from the National Mosque, and mere blocks from Petaling Street, the famous haggler corridor. When I first checked in, I was greeted by Max, the 40-something portly Palestinian manager who seemed to dislike everyone and everything, especially Kuala Lumpur. If you’ve spent much time in hostels, you’ve probably met someone like Max before. With slouched shoulders and a perpetual smirk , Max was a full-time (as in he seemingly *never* left!) resident of the hostel, lounging about in grey sweatpants and occupying a small, windowless room next to the reception desk. He had masochistically decided to dwell in that hostel, alternating between the reception desk and his bedroom, a long time ago.

Max wasted no time explaining that Malay employees were “unreliable,” claiming that they stole from the hostel all the time. So he was obligated to manage the place all by himself. He also told me that Kuala Lumpur was a very dangerous city, and it was rife with low-lifes, like pickpockets who snatched people’s bag from motorbikes. And, since I was a petite solo female traveler, I was unsurprised to find that Max assumed I was completely naive and bewildered. After explaining that I couldn’t drink the tap water, and that the electric outlets were different from the States, and going over every possible inconvenience, I decided to ignore Max’s warnings and walk through the supposedly explosive, gang-ridden streets of Kuala Lumpur. In reality, Kuala Lumpur is safe — very safe. After one month in the Philippines, I felt like I was walking through a Hollywood studio set; everything was so clean and light on traffic. Now, this isn’t to say that Kuala Lumpur is free of issues. But let’s just say that KL is pretty damn orderly.

Anyway, first stop: food. This was the moment that I had been waiting for. In Chinatown, I walked down Jalan Tun Tan Cheng Lock, where I quickly selected one of many restaurants. The waiter handed me a plate stacked with steaming white rice. I was then signaled to choose from maybe eighteen pots of food — things like tandoori fried chicken, fish head curry, fish cooked in coconut milk, meat stews marinated with tamarind and chili, rendang, satay, and of course the beloved naan and roti. The sheer variety of food was mouth-watering. And, at this restaurant, I was offered not one type of cuisine, like Malay, Malay-Chinese, Malay-Indian or Nonya, but a fusion of influences. Though I was new to town, and I didn’t quite know what I was eating, I did know at least one thing: this food was cheap. Surprisingly cheap. That night, I learned that food in Malaysia costs just as much, oftentimes even less, than food in the Philippines, a significantly poorer country.

The next morning, in the unrelenting Kuala Lumpur heat, I played tourist. Yeah, I saw the Petronas Towers. I walked through Chinatown and the Masjid Jamek district, visiting Chinese Buddhist temples and Malay mosques. And I ate more scrumptious meals. But, by evening, I was ready to make local friends. So I decided to turn to CouchSurfing, even if tons of creepy dudes who are one step above sending dick picks prowl that site. Fortunately, there was an event happening that night. So, I decided to take a gamble and RSVPed .

Later that night, as I was about to leave for the CS meeting, I saw Max, sitting at the reception desk, as usual. I asked, “Hey Max, what time does the subway close?”

“Oh, about 11:30. But are you sure you want to go out?!” Max asked with a concerned look in his eye, like I was a baby deer. “It can be very difficult for you to get home, and that could be dangerous for you.”

“It’s 8 pm. I’ll be fine.”

“Are you sure?” he asked with a troubled frown. He must have been thinking, how could this tiny, defenseless foreign woman ever find her way back to the guesthouse? How could she avoid the roving motorbike gangs of Kuala Lumpur?

“Yes, Max, I’ll be fine.”

Soon enough, I was walking down Jalan Nagasari in the Bukit Bintang district, looking for a nondescript restaurant. This was because in Malaysia, as it turned out, people seem to think it’s unnecessary to list the building number in an address. They often just list the street name — and this CS event was no exception. After walking up and down the street at least twice, I finally found the restaurant, which advertised “Arabian,” “Western,” “Thai Seafood,” and “Masakan Melayu” (Malaysian food) on its red banner. And, when I walked inside, there they were: that awkward group of outsiders, the CouchSurfers. They would be from places like Canada and Jordan, Italy and Miami, along with a good amount of Malaysians. And what they all shared in common was some irrepressible need to meet strangers, as uncomfortable as it may be.

Taking a seat at one of the tables, I listened to someone explaining that he was Malaysian, even though his background was Chinese. This goateed American at the table didn’t understand, and kept on annoyingly asking, “Where in China are you from?” Ugh, didn’t he have any understanding of the place that he was visiting, and didn’t he notice that many Malaysians were ethnically Chinese? As the Malaysian guy tried, yet again, to explain that he was Malaysian, and not from China, I scoured the table for other, possibly cooler, attendants. There was an Iraqi engineer, who was young and amiable, a Polish girl who lived in Hanoi with the goateed American (her boyfriend), a pudgy Indian Malaysian in a business suit, and some others.

I began to explain that I loved the diversity of Kuala Lumpur — how Malay, Indian and Chinese cultures intermixed. Then the Indian Malay businessman turned to me and said, “Ah, we’re not so diverse! Now, where you’re from — North America — that’s diverse. I used to think we were diverse here in KL. Everyone says, ‘Malaysia is so diverse!’ Then I visited the US and Canada, and I don’t think we’re so diverse anymore,’” After some discussion, it was agreed that Malaysia was comparatively diverse for the region.

Then another dude, who I would later learn was named Krishna, sat down at the table. He seemed to burst out of nowhere, shoving his head into our conversation, spontaneously delivering anecdotes about social science, history, food and other subjects spoken with a geeky effulgence. Over the course of the night, I began to speak with Krishna more than anyone else, and I learned that he was originally from Chennai, though he had lived in Laos and many other places. He worked in marketing at an IT company, and he was happy with KL, though he stated without reservation that Malay people had a “bad work ethic,” a seemingly common, yet troubling, dismissal of the local people that was found among many expats, such as Krishna and Max.

When I said I needed to head back to my guesthouse, since Jared was arriving that night, Krishna offered to drive me home. We walked back to his car, passing bars filled with raucous white tourists, drinking at Western-style pubs with cheesy Irish themes.

“That’s all you guys come here to do,” Krishna joked.

“You mean, white people just come here to drink?”

Krishna nodded in agreement. We then discussed my previous job at a software company in New York. Krishna seemed astounded — how could I leave a “good” job behind? He assumed most Western backpackers were burnouts, or people who had never worked in a high-pressure corporate environment. He didn’t understand why I left an apartment in Manhattan, or a decent salary in a thriving field, so I simply said that I wasn’t happy enough in my career path. We soon reached the parking lot, where Krishna had a heated confrontation in, I guess, Tamil with another Indian dude who managed the lot.

“The Indian mafia,” he sighed. “They run the parking lots here.”

Construction in the merciless KL heat. This picture was taken on our walk to the Islamic Arts Museum.

During our car ride, it was confirmed that Krishna would host a party at his apartment the following night. All of the CS regulars of KL were invited, and so were Jared and I. After I was dropped off at the guesthouse, I waved hello to Max, sitting at the reception desk. He reminded me of a stubborn toad, grudgingly guarding his lilypad. He had been sitting at that desk since 8 in the morning, and he was still there, past midnight. Since, you know, he had to guard the place against robber barons and fierce drug lords.

About an hour later, Jared finally arrived at the hostel, and I was thrilled to see him again. We swapped travel stories, talking about his last days in Manila, and my comparatively lax experiences in Cebu and Kuala Lumpur. And I told him that we were invited to a party the next evening.

Oh, and I told him about Max. Since Max was creepily paternalistic, I joked that maybe he was one of those perverted hotel managers who spy on on unsuspecting guests from secret peepholes into their rooms. But, in all honesty, Max was starting to grow on me by that point. He had offered me tea in the morning when he noticed my persistent cough. And, even better, he seemed much cooler than I had imagined.

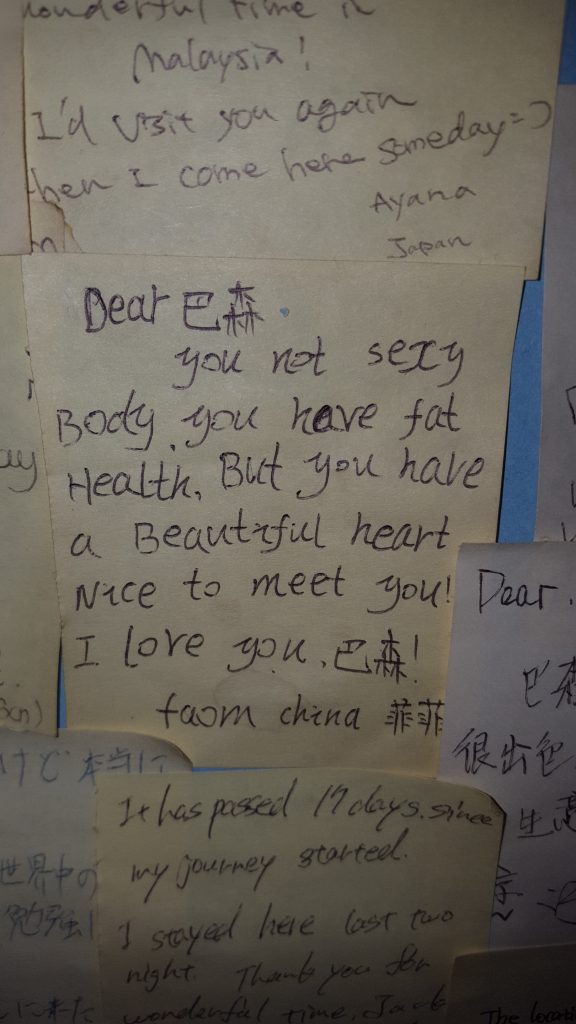

You see, there was a wall of “thank you” notes in the hostel, and Max had enough sense of humor, or “fuck it” attitude to post the following note, written by a Chinese guest on the wall: “Dear [and then something in Chinese, which I guess meant ‘Max’], You not sexy Body. You have fat Health. But you have a Beautiful heart. Nice to meet you! I love you, Max. From China.”

The next day, we visited the Batu Caves, a series of Hindu shrines built in the caves of a 400-million year old limestone hill. There’s the Temple Cave, the main cave, which features a massive golden statue of Murugan, the Hindu god of war, and requires a climb up 272 steps. Everyone takes a picture in front of the shrine’s steps; it’s like the Eiffel Tower shot of Malaysia. But the Ramayana Cave was our personal favorite. The cave tells the epic tale of Rama through an extensive series of statues, each depicting scenes from his life, such as Rama’s marriage to Sita, the couple’s fourteen-year exile, Sita’s abduction by the demon king Ravana, and Rama’s rescue of his beloved wife. It’s an imaginative, almost psychedelic way, to learn about the Hindu epic poem, Ramayana. But, within about thirty minutes into our cave visit, the rain began to pour. Lightning and thunder — the works.

I sent a message to Krishna: “It’s raining really bad. Is the party still going on?”

He seemed amused. “It’s Malaysia! It rains like every day here,” he said. “Everybody is still coming.”

We headed back to our guesthouse, soaked in rainwater, quickly changed, and headed to the party. Krishna’s yuppie high-rise apartment was located in a KL suburb, where sports cars and doormen were a commonality, including in Krishna’s building. Once we arrived at the party, we found that it was, just like Krishna promised, full of people. No thunderstorm was a biggie, it seemed, in Malaysia. We sat down and began to mingle with the guests. One of the most interesting guys was named Darshit, an Indian Malaysian dude, probably in his early 30s, who freely discussed details of American political history, comparing the Presidents with the historical knowledge and grace of someone who clearly knew his shit. He briefly mentioned that he had been accepted to Harvard Business School but couldn’t afford it, and he couldn’t understand how anyone could afford school in America.

The goateed American guy was also at the party. As we all discussed American politics, the American interjected, “I just heard Ted Cruz speak the other day; I had no idea who he was!” By his tone of voice, I could tell that he felt very proud of his ignorance, as if his expatriate lifestyle had rendered him above American political squabbles. As if he was no longer American, and no longer needed to care about the States, or its politics, or its impact on the world. When I asked why he hadn’t heard of Ted Cruz, the American explained that he had been out of the country for five years, so he didn’t know what was going on. What the hell? Probably half the people at the party, none of whom were American, could eloquently speak on the subject of the 2016 Presidential election, and this guy had nothing to say?

Jared in Kuala Lumpur’s Chinatown, waiting for our Uber to arrive. Quick tip: If you want to avoid taxis charging you like 3 times the normal price, since you’re a dumb foreigner, Uber works in lots of Southeast Asian cities, like Manila, Kuala Lumpur and Jakarta, and is always a standardized price.

At any rate, the party was dying down, and a group of guys decided to go bar-hopping, KL style. The core group included Jared, Darshit, Dewitt, a Malay guy with a posh accent and preppy outfit, and Vin Diesel (I honestly don’t know his real name), as he was called, a muscular half-Chinese, half-Indian KL local, and me. When we announced that we all wanted to go bar-hopping, Krishna looked crushed. I asked if he wanted to come, “No,” Krishna emphatically stated. “I know how clubbing in KL goes. You spend a ton of money, you talk to absolutely no girls, and you go home alone. Anyway, the type of girl that I want to meet wouldn’t be at a bar.” I was pretty drunk so I sarcastically asked, “Where would you meet her? At a software conference?” Krishna’s eyes brightened. “Yes, in fact, I did meet a girl at a software conference once!” he beamed, though I doubted anything actually happened.

Then, Krishna turned to the entire party: “These people,” he regally announced, motioning toward all of us, “want to go out bar-hopping in KL. But, if you prefer to stay behind and have some nice, civilized conversation, we will continue the party here.” The Polish girl looked secretly interested, but her boyfriend, the America, said he preferred the civilized conversation, so the Party Group left.

We packed into Vin Diesel’s car and everyone exclaimed they were glad to be out of the party. They teased the American guy, calling him “Kenny G” because of his cheesy disposition and long hair. Then the guys began discussing which bars were the best for our night out. Well, there was one with a speakeasy vibe, and another with a loungey vibe, and soon they were discussing KL nightlife at a breakneck pace that I didn’t understand. At any rate, they eventually explained, “We don’t like to go out in Bukit Bintang. We prefer the suburban areas that are calmer and nicer, you know.” I took “calmer and nicer” to mean richer, and I was right.

Now, if you’re unfamiliar with Bangsar Baru, it’s where the upper-crust of Kuala Lumpur live — I’m talking CEOs, expatriates in the international finance and diplomatic set, and the kinds of Malaysians who speak English with a British prep school accent. So, it was at this point in the evening when things took a dramatic turn, and we entered the world of the Malaysian Uber-Rich. Our group walked up to a bar/club, where Dewitt and Vin Diesel sweet-talked the doormen. The doormen agreed to let us inside, and so we entered Mantra Rooftop Bar, a socialite’s party paradise, consciously syrupy and spacious, dimly lit with trendy purple lights and plush lounge sofas, where the DJ played Western hip hop and pop singles, though nobody seemed interested in dancing. We opted to drink on the rooftop balcony, which exposed a gorgeous panoramic view of the neighborhood below. Aside from classic cocktails, the drink menu included Mantra originals, with names like Dynasty, Mantra Tonique No. 10 and Mekong Sunset.

Sitting in a ridiculous hammock chair, observing these incredibly privileged rulers of the city, I had a flashback to my former life in Istanbul. It was a completely different city, and a completely different time in my life, but Istanbul was the last time I remembered going to crazy swanky rooftop bars like Mantra. There was something about being foreigners or outsiders, just like in Istanbul, that had enticed these wealthy and exclusive people to invite Jared and I into their lives. And, so we drank chic cocktails, talked over the rap music, and discussed politics, travel and work, including the fact that Dewitt’s dad sold planes, and that he traveled to Singapore and Thailand for work constantly, and oh you know, the usual.

After some drinks, Dewitt decided to talk to a girl, and Vin Diesel followed him as back-up. But, as he glided across the balcony, Dewitt stopped in his tracks and began to spontaneously and energetically hug a group of people. A few minutes later, he excitedly rushed back to our table. “My sister and cousins from Australia are here!” he exclaimed. I guess that’s also normal — running into other rich people at swanky lounges. “Let’s go sit with them!”

We moved into the interior area, where we sprawled across sumptuous couches, and the Australians ordered a bottle of Belvedere vodka for the table. “That’s really nice vodka,” Jared whispered to me. “Drink as much as you can.” Dewitt’s sister was beautiful — a sort-of pouty rich girl beauty that seemed prepared to marry very, very well. The cousins were Aussie casual-style, and they talked about travel, and about the bar they owned in Perth, and we got drunker and drunker, until I found myself dancing with Dewitt to some trashy rap song, and of course we were the only ones dancing in the entire damn place. Meanwhile, Jared networked with a young Aussie millionaire who sincerely discussed his family dynamics, and was intent to hear Jared’s opinions on his latest business ventures. This hedonistic, vodka-infused haze lasted till about 3 am, at which point the bar closed down and I was ready to go home.

But no. We couldn’t go home just yet. Dewitt insisted that we visit another upscale bar, though this one was decorated to seem like a neighborhood bar — or, more accurately, a casual American bar, if it was filled with only rich Malaysians. By this point, our group consisted of the original four, the members of Dewitt’s family, and a very chatty Chinese Malaysian girl who worked in the fashion industry or whatever, and smoked like rich girls of 1980s Hollywood movies. Dewitt and his cousins insisted we take more shots. Both Vin Diesel and I were absolutely finished with alcohol, so we pretended to take our shots, but Jared finished them for us. Things started getting really messy, and I was ready to go home. At 4 am, I requested an Uber.

“Hey, we’re going now. Our Uber’s here!” I told the group.

“Noooo,” Darshit began, “I promised I would take you to a fantastic restaurant in the neighborhood after we went out drinking!” We had drunkenly decided to eat food, many hours earlier, when the vodka was newly settled in our stomachs, and when our energy wasn’t depleted. I really didn’t want to eat at that point. But Darshit’s eyes begged us, puppy dog-style, to stay. “Can you cancel your Uber?” he pleaded.

“Okay, sure,” I said, and I cancelled the Uber. We finally bid goodbye to the group, which was beginning to resemble a frat party gone very, very wrong, with Dewitt on the verge of falling down for the twentieth time. Then, Jared, Darshit and I headed to Nasi Lemak Famous, touted to be the best vendor of Nasi Lemak, the national dish of Malaysia, in the city. Now, it was 4 am at this point. I was tired and coming down from massive amounts of alcohol, but I thought the food was divine. Of course I ordered the nasi lemak, making sure to cover the rice with ample amounts of the anchovy hot chili paste. I can’t recall what we discussed over that meal. We just ate and talked, ate and talked. It was the best way to end the night.

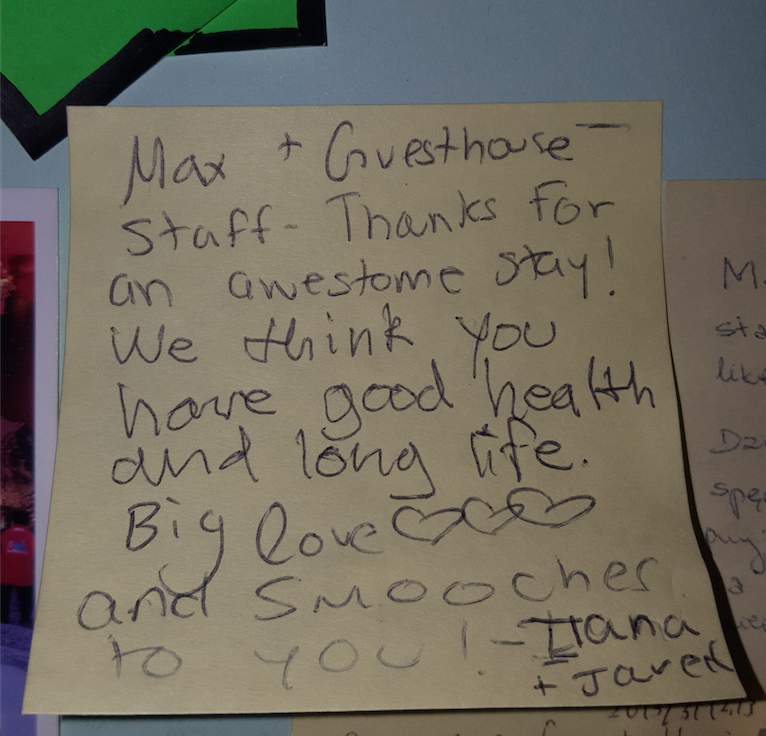

Finally, at 5 am, we requested another Uber, and Jared and I finally returned to Chinatown. We collapsed into bed — and, the next morning, we were too decimated to leave town, as we planned, so we spent another day in KL, recovering from the worst hangover of our trip. Once we were finally ready to go, we had one last thing to do: write a note to Max. He had become a sort of lovable, if rather disgruntled, father-figure to the guesthouse, offering cough drops and late night tea, quietly judging us with his eyes when we came back home past midnight. And now was our time to say goodbye to Max, this curmudgeonly, perhaps secretly good-humored, man of Kuala Lumpur. “Max and Guesthouse Staff,” we wrote, “thanks for an awesome stay! We think you have good health and long life. Big love and smooches to you. Lani and Jared.”

Leave a reply